Vetscape Game Changers

We’re sitting in an office at the Vetscape Animal Hospital in Paarl. There are no fancy accessories or lounge chairs, just two Godolphin paintings on the wall. There are book shelves which hold files, medical records and subjects which relate to, well, specialist veterinary topics. Three computers stand on one side of the room, all warm from the amount of work they are put through. On another side is what looks like a makeshift coffee and tea station, and a small fridge. This office doubles as a kitchen.

We gather around the table which is clear, except for a printed schedule and TV times of Rugby World Cup matches. It’s a reminder that even for the most dedicated and hard-working veterinary team, the pressure cooker has to have a lid.

This wasn’t always an office. In fact, it was the ICU room where the five-time South African champion sire Jet Master passed away in 2011 following an operation to help him regain his co-ordination after he had been affected by cervical vertebral instability. “Unofficially, we call it the Jet Master lounge, in honour of the legend. He made it through the operation but not the ordeal,” says Dr Andrew Gray, a specialist equine surgeon.

His career has evolved after graduating from Onderstepoort in 2002, to an emergency night vet at CAMC, followed by a stint at Cape Vets based at Milnerton Racecourse. He spent time in Australia before relocating to Paarl, where he and his wife, Tacita are raising their four children.

“My sister is also a doctor, but a human one,” he laughs. “She works extremely hard, but fewer hours than me, and she earns a lot more money.” There’s a smile on his face as he talks, although the eyes light up when it comes to his work. What is that expression? It’s not a job if it’s a passion?

The stubble around the face suggests he hasn’t shaved this particular morning, but that’s understandable. Long days and nights at work, then going home to fulfill the role of doting father and husband, isn’t going to leave much time for even the basics.

This is the busiest time of the year for the hospital. “It’s definitely ‘in-season’,” Dr Gray says. “It’s foaling season and there are many associated risks, with post-foaling mare issues and sick foals being the most common.”

In fact, as we’ve done a tour of the facility, we’ve come across mares with their young, recovering from illness or surgery. Some of whom are household names to those involved in the racing industry, champions on the track who are now producing the champions of tomorrow. Obviously, given the confidentiality between clients and the hospital, we are not naming them, except to say that illness and recovery – and occasionally death – surrounds us.

“It’s no different to a human hospital,” Dr Gray says. “Just like people don’t go into hospital unless they are really ill, horses don’t get admitted into Vetscape unless they have serious issues. People can die in hospitals – and our equine patients carry that risk too.”

The “we” I refer to on the occasion of this visit are the Kuda Insurance team of bloodstock manager Jo Campher and Tammi Grieve, head of marketing and branding. My role? To tell it like it is.

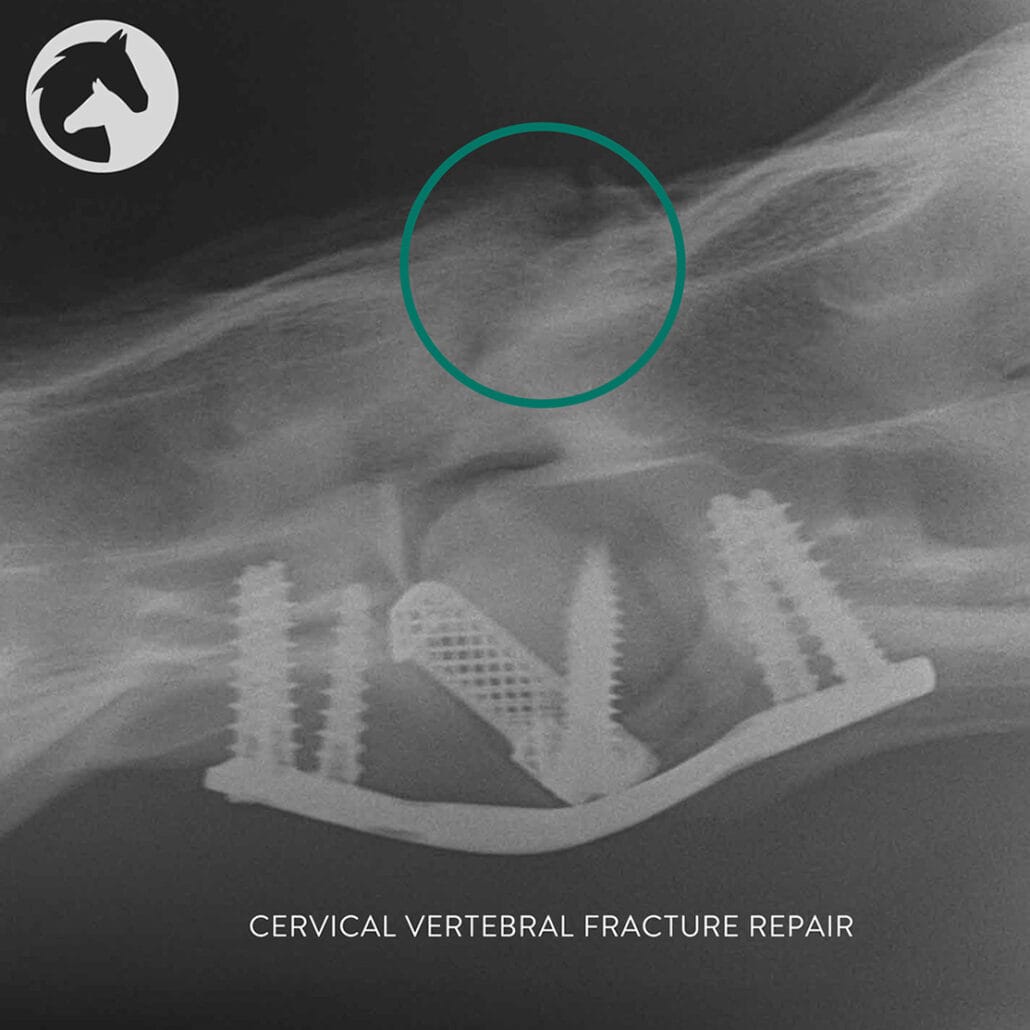

This particular connection between Kuda and Vetscape is centred around two horses, a 2021 yearling and a filly now named Amasova. The yearling was in the process of being prepped for the KZN Yearling Sale when she fractured her neck, which is a more common occurrence than one thinks. Traumatic cervical vertebra (neck) fractures may be caused when a horse rears up and flips over, runs into a solid object like a pole or wall, or suffers blunt trauma from paddock mates, such as a kick or collision. Often there’s immediate fatality, or paralysis.

“Her vertebra collapsed in on her spinal cord. This caused, severe incoordination and pain and it became difficult for her to get up and move around,” says Dr Gray. “After isolating the fracture and site of compression, we carefully stabilised the two affected vertebrae with a custom-made titanium cage, reinforced with a broad plate and screws at the level of C5, C6. When fusing two bones it takes about six months before a solid boney bridge forms. If you stress the implant in that time, the bones move and the screws become loose. The challenge is getting that boney bridge between the two vertebrae to fuse,” he says.

The other case involves Amasova, a confirmed Wobbler. “She presented to us when she got a virus that affects the central nervous system,” says Dr Gray. “Wobbler cases are much more sensitive to neurological viruses. When Amasova remained severely ataxic (often struggling to get to her feet) after recovering from the virus, we investigated further. X-rays and a myelogram of her neck confirmed focal compression on the spinal cord due to intervertebral instability (referred to as a Wobbler). The decision was made to operate and a C4, C5 vertebral fusion was performed. For this particular surgery, a titanium cage, rods and pedicle screws were used.”

This was also a resounding success and Amasova recently tested in foal to former Horse of the Year and multiple Equus winner Legislate.

An agreement between Kuda insurance and clients Cheveley Stud, and an arrangement with Vetscape to “meet in the middle” from a cost perspective, led to Dr Gray’s involvement.

“Amasova was very unstable, and had no chance of a racing career,” explains Janine Koster, Kuda’s division head of niche products.

“In the case of Amasova, there had to be willing parties to move forward with surgery. Kuda, as insurers, had to be willing, as did Cheveley Stud, Vetscape and SA Spine, who manufacture the spinal implants. All angles needed to be explored, and it helped that in making the decision it was with parties who have an intimate knowledge of the industry, in order to partner,” Koster said. “This was a case of our life saving surgery and critical care offering being utilised to help create a success story,” she added.

Again, we won’t reveal the extent of the cost of the operations and add-ons, suffice to say that both Kuda and Vetscape were working towards a common goal. That goal is to ensure end-result surgery and recovery for similarly affected horses with Wobblers as much more of a standard procedure.

“We are already making great progress,” says Dr Gray. “The first operation took four hours and the second was about half that. The more of these procedures we perform, the shorter the operating time will be until we get it down to between 90-120 minutes. It’s an extremely intricate operation, so the horses have to be under general anesthetic and completely immobilised and secured.”

He explains what a Wobbler is in layman’s terms. “There are four grades to the condition. Grade 1 is when it is only felt when ridden at work. The jockey may say that the horse feels unstable behind. It’s difficult to motivate surgery at this stage, although overseas they do operate quite often at this stage. Grade 2 is when the horse is uncoordinated while walking. Grade 3 is when it’s dangerous for a person to walk next to it, and euthanasia is often discussed. Grade 4 is when a horse can’t get up, it is recumbent (laying down).” Amasova was hovering between Grade 3 and Grade 4.

Dr Gray explains what is ground-breaking about the yearling and Amasova. “We are constantly trying to advance the scope of our work. At Vetscape, we’re always looking to push the boundaries in equine surgery and medicine. Cervical (neck) surgery is well established in other equine centres across the world and what we are doing here is novel. We’re customising implants and developing new techniques. Gert Bekker, engineer and owner of SA Spine, is instrumental in the process. He knows implants. He custom manufactures everything in Pretoria. It has created a unique relationship between us as vets, Kuda as insurers and SA Spine, the suppliers. Every operation we now perform improves on the previous one.”

“Historically, there were different techniques with less favourable outcomes and higher mortality rates. Now it’s all changed, with custom-made implants. If you engineer something specifically to fit the bone, it’s much better than a straight plate on curved bone. We are reaching the stage of acquiring 3D images of horse’s cervical vertebrae, which helps, because necks aren’t all the same. This is a whole new frontier that we’re encountering.”

Frontiers, challenges and progress are what Vetscape is all about. “There was a time when any horse that fractured a limb would be euthanized,” Dr Gray says. “Now we frequently repair limb fractures and can almost guarantee a reasonable success rate, when it’s a fracture ‘realistic’ enough to operate on. That is what we are striving for with cervical vertebral surgery, and post-operative success rate. If we can do that, it’s going to be better for the horse and better for the owners”.

In short, Dr Gray, with help from other role-players, is determined to make strides forward in equine surgery. And, he’s doing it with untapped enthusiasm and a smile on his face.